Since 2021, I have been working in partnership with the National Trust and Artes Mundi to respond to the Clive Museum collection at Powis Castle. Below are a series of posts relating to this work.

The exhibition resulting from this partnership is currently on display at Powis Castle, Welshpool.

The exhibition resulting from this partnership is currently on display at Powis Castle, Welshpool.

The Spirit of the Tiger

I’ll never forget Khitish telling me that there were members of tribal groups in India who could turn into tigers (Khitish was one of the hosts on the RI/ACE Arts and Crafts Exchange to Odisha I attended in 2013). He was adamant that this was the case, and talked about the sacred knowledge held by the Adivasi (indigenous communities). My rational brain struggled to accept what he was telling me but he made a long and impassioned argument that at least had me questioning the limits of my knowledge.

The tiger has held the fascinations of people and culture for thousands of years. It has a particularly important place in the religions, cultures and mythologies of Inida, and Asia more widely. However, the tiger also managed to weave itself into the Western imagination and can be seen in many medieval bestiaries. The following is an extract from The Bodley Bestiary produced around the middle of the 13th century.

The tiger has held the fascinations of people and culture for thousands of years. It has a particularly important place in the religions, cultures and mythologies of Inida, and Asia more widely. However, the tiger also managed to weave itself into the Western imagination and can be seen in many medieval bestiaries. The following is an extract from The Bodley Bestiary produced around the middle of the 13th century.

|

The tigress, when she finds her lair empty by the theft of a cub, follows the tracks of the thief at once. When the thief sees that, even though he rides a swift horse, he is outrun by her speed, and that there is no means of escape at hand, he devises the following deception. When he sees the tigress drawing close, he throws down a glass sphere. The tigress is deceived by her own image in the glass and thinks it is her stolen cub. She abandons the chase, eager to gather up her young. Delayed by the illusion, she tries once again with all her might to overtake the rider and, urged on by her anger, quickly threatens the fleeing man. Again he holds up her pursuit by throwing down a sphere. The memory of the trick does not banish the mother's devotion. She turns over the empty likeness and settles down as if she were about to suckle her cub. And thus, trapped by the intensity of her sense of duty, she loses both her revenge and her child.

|

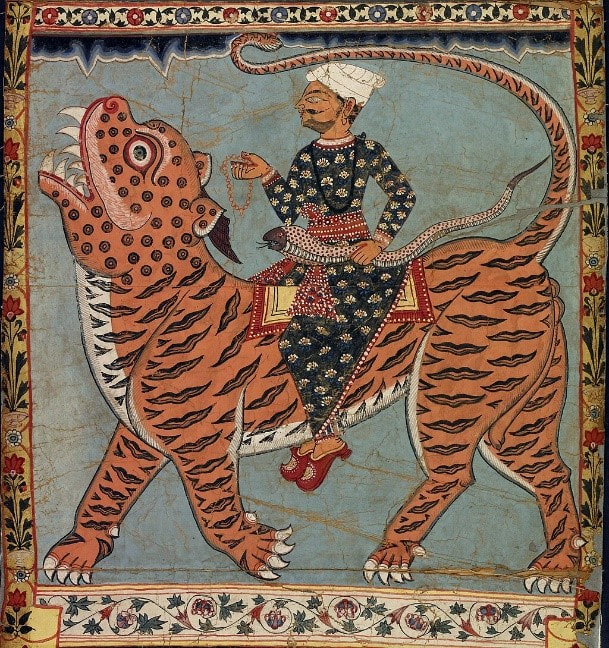

Tipu Sultan known by the British as the ‘Tiger of Mysore’ famously used the symbol of the tiger as his personal emblem. Tipu would have been aware of the syncretic religious and cultural environment in which he was operating. The relationship between the power of divine beings which was claimed and exercised by kings and rulers was important during the time Tipu ruled.

In the Muslim tradition this power is represented by the Sufi warrior Gazi Pir who lived in the 12th or 13th century and was credited with spreading Islam in Bengal. His life is shown in the Gazi scroll (a series of 54 paintings) held by the British Musuem. He was known for his power over dangerous animals and controlling the natural elements. Villagers living in the Sundarbans worship Gazi Pir to ask for protection from tigers.

In the Hindu tradition this power is represented by the warrior divinities Durga and also Kali. The tiger is the principle vehicle (vahan) of the Hindu goddess Durga who uses her power to combat the evil that threatens peace and prosperity. She is also a liberator for the oppressed, and uses destruction to empower creation.

The use of the tiger by Tipu Sultan essentially represents the activation of divine power.

In the Hindu tradition this power is represented by the warrior divinities Durga and also Kali. The tiger is the principle vehicle (vahan) of the Hindu goddess Durga who uses her power to combat the evil that threatens peace and prosperity. She is also a liberator for the oppressed, and uses destruction to empower creation.

The use of the tiger by Tipu Sultan essentially represents the activation of divine power.

In Fragments from a Crtical Dictionary of South East Asia, Ho Tzu Nyen suggest that following the ecological and cosmological massacre that British colonial rule brought in Malaya, Weretigers were exiled to the realm of folklore. However, he goes on to suggest that the tiger undergoes ceaseless reconfiguration to haunt the region in the form of resistance, first by Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita (The Tiger of Malaya) and then by the Malayan Communist Party.

‘To embark upon the trail of the weretiger is to follow through with its line of perpetual metamorphosis – an anthropomorphic, yet non-anthropocentric line that is at once materialist and metaphorical’.

What is palpable for me is that the spirit of the tiger endures and continues to manifest itself as a symbol of resistance and liberation, as seen in the following works.

Remembering a Brave New World was Tate Britain’s Winter Commission for 2020. Artist Chila Burman installed neon lights onto the neo-classical façade of Tate Britain referencing Indian mythology, popular culture, female empowerment, political activism and colonial legacy. One of the neon images she chose was that of a Bengal Tiger, a remembered image from her father’s ice cream van. The commission also coincided with Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights. Placing these counter cultural memories onto a Western art façade creates a certain tension, perhaps highlighting the need for dialogue and conversation. The festival is about the light at the end of the tunnel, about good over evil.

The title of the works draws its inspiration from Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel, A Brave New World. Unlike Huxley’s dystopia, Burman suggests that inspiration can be found in the past offering a sense of hope for the future and faith for a brave new world.

‘To embark upon the trail of the weretiger is to follow through with its line of perpetual metamorphosis – an anthropomorphic, yet non-anthropocentric line that is at once materialist and metaphorical’.

What is palpable for me is that the spirit of the tiger endures and continues to manifest itself as a symbol of resistance and liberation, as seen in the following works.

Remembering a Brave New World was Tate Britain’s Winter Commission for 2020. Artist Chila Burman installed neon lights onto the neo-classical façade of Tate Britain referencing Indian mythology, popular culture, female empowerment, political activism and colonial legacy. One of the neon images she chose was that of a Bengal Tiger, a remembered image from her father’s ice cream van. The commission also coincided with Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights. Placing these counter cultural memories onto a Western art façade creates a certain tension, perhaps highlighting the need for dialogue and conversation. The festival is about the light at the end of the tunnel, about good over evil.

The title of the works draws its inspiration from Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel, A Brave New World. Unlike Huxley’s dystopia, Burman suggests that inspiration can be found in the past offering a sense of hope for the future and faith for a brave new world.

Zadie Xa’s work, House Gods, Animal Guides and Five Ways 2 Forgiveness currently showing at the Whitechapel Gallery is an installation comprised of sculptures, textiles and paintings. Korean mythology and folklore permeate the work providing a narrative framework to explore systems of power, home and belonging.

Various animals are present throughout the work. ‘The artist perceives animals as avatars; embodiments of ecological, political and cultural shifts within our world’.

In fables across the world, animals are often protagonists who help instruct society or highlight power structures and moral quandaries. The presence of the tiger in Xa’s work reflects her exploration of the ‘trickster’ archetype within folklore: it represents a disruptive outsider whose presence provokes and inspires change from dominant social and cultural orders.

Although I may never believe that there are people that can turn into tigers (as much as I would like to), I sense that the spirit of the tiger lives on. Symbolically, the tiger still holds power which can be harnessed and drawn upon by individuals, as it has done throughout history.

Various animals are present throughout the work. ‘The artist perceives animals as avatars; embodiments of ecological, political and cultural shifts within our world’.

In fables across the world, animals are often protagonists who help instruct society or highlight power structures and moral quandaries. The presence of the tiger in Xa’s work reflects her exploration of the ‘trickster’ archetype within folklore: it represents a disruptive outsider whose presence provokes and inspires change from dominant social and cultural orders.

Although I may never believe that there are people that can turn into tigers (as much as I would like to), I sense that the spirit of the tiger lives on. Symbolically, the tiger still holds power which can be harnessed and drawn upon by individuals, as it has done throughout history.

References

1. Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 764https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/ecf96804-a514-4adc-8779-2dbc4e4b2f1e/surfaces/0f7fc8ff-7493-4101-a292-49da644b6a13/

2. The Power of Tipu's Tiger. An Examination of the Tiger Emblem of Tipu Sultan of Mysorehttps://www.jstor.org/stable/312813

3. the critical dictionary of south-east asia (cdosea.org)

4. Interview | ‘Blinged-up but razor-sharp’: Chila Kumari Singh Burman on her Diwali-inspired Tate Britain commission (theartnewspaper.com)

5. https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/zadie-xa-house-gods-animal-guides-and-five-ways-2-forgiveness/

1. Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 764https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/ecf96804-a514-4adc-8779-2dbc4e4b2f1e/surfaces/0f7fc8ff-7493-4101-a292-49da644b6a13/

2. The Power of Tipu's Tiger. An Examination of the Tiger Emblem of Tipu Sultan of Mysorehttps://www.jstor.org/stable/312813

3. the critical dictionary of south-east asia (cdosea.org)

4. Interview | ‘Blinged-up but razor-sharp’: Chila Kumari Singh Burman on her Diwali-inspired Tate Britain commission (theartnewspaper.com)

5. https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/zadie-xa-house-gods-animal-guides-and-five-ways-2-forgiveness/

Powis Castle as a site of learning, social cohesion and healing

I am writing this blog post during South Asian Heritage Month and am going to start with its conclusion. Given the lack of formal education surrounding colonisation and empire in schools, Powis Castle, particularly the Clive Musuem, and other heritage sites of a similar nature become critical sites of learning and disemination. There is a social and moral obligation to ensure that colonial history is told, both from the perspective of the coloniser and colonised. In doing this, Powis Castle has the potential to become a site of social cohesion.

When I visited Powis castle in 2021, I realised how little I knew about the origins of the colonisation of India. My knowledge of the East India Company was limited and I only had a general awareness of Robert Clive’s significance. I also knew very little about Tipu Sultan.

After this visit, the learning began but the process all felt a little distant, academic and objective. What I really wanted was a better understanding of the ramifications of the historical actions and how they interacted with the present day. I wanted a bridge from the colonial past into the present.

Having learned more about the historical events, informed by post colonial theory and following some reflection, I felt more confident to follow strands of the past into the present. I became interested in how the privileges and oppressions of empire played out historically, continued through time, and in some cases into the present day. I also became interested in the relationship between my family history and the actions of Robert Clive, the East India Company and the subsequent colonisation of India.

During my visits, I also became interested in the interpretation within the Clive Museum and whether it presented a skewed narrative. It certainly doesn’t feel balanced. The interpretation has changed over time and is still in the process of being developed. For me, it still feels a little distant, objective and impersonal. I would like to see more South Asian voices, more personal voices. I feel it is critically important that the voice of the coloniser and colonised are equally represented. I’d also like to see a stronger bridge built between the past and the present within the interpretation. What are the the ramifications of Robert Clive and the East India Company’s actions?

During my visits to the Clive Museum I was intrigued to hear the conversations between volunteers and members of the public. Increasingly, I have thought about how critical a role these volunteers play in conversations about colonialism and empire. With the lack of formal education around empire mentioned earlier, these volunteers become important informal educators.

I delivered a talk to staff and volunteers. It was interesting to hear about how they handled tricky conversations around colonisation. It was clearly difficult for volunteers because there wasn’t necessarily a definitive position from the National Trust surrounding the collection. e.g. should cultural artefacts within the collection be repatriated? The knowledge, training and support that these volunteers receive seems to be of paramount importance. I heard from the volunteers that holding potentially emotionally charged conversations in the wake of a polarised media was no easy task.

When I visited Powis castle in 2021, I realised how little I knew about the origins of the colonisation of India. My knowledge of the East India Company was limited and I only had a general awareness of Robert Clive’s significance. I also knew very little about Tipu Sultan.

After this visit, the learning began but the process all felt a little distant, academic and objective. What I really wanted was a better understanding of the ramifications of the historical actions and how they interacted with the present day. I wanted a bridge from the colonial past into the present.

Having learned more about the historical events, informed by post colonial theory and following some reflection, I felt more confident to follow strands of the past into the present. I became interested in how the privileges and oppressions of empire played out historically, continued through time, and in some cases into the present day. I also became interested in the relationship between my family history and the actions of Robert Clive, the East India Company and the subsequent colonisation of India.

During my visits, I also became interested in the interpretation within the Clive Museum and whether it presented a skewed narrative. It certainly doesn’t feel balanced. The interpretation has changed over time and is still in the process of being developed. For me, it still feels a little distant, objective and impersonal. I would like to see more South Asian voices, more personal voices. I feel it is critically important that the voice of the coloniser and colonised are equally represented. I’d also like to see a stronger bridge built between the past and the present within the interpretation. What are the the ramifications of Robert Clive and the East India Company’s actions?

During my visits to the Clive Museum I was intrigued to hear the conversations between volunteers and members of the public. Increasingly, I have thought about how critical a role these volunteers play in conversations about colonialism and empire. With the lack of formal education around empire mentioned earlier, these volunteers become important informal educators.

I delivered a talk to staff and volunteers. It was interesting to hear about how they handled tricky conversations around colonisation. It was clearly difficult for volunteers because there wasn’t necessarily a definitive position from the National Trust surrounding the collection. e.g. should cultural artefacts within the collection be repatriated? The knowledge, training and support that these volunteers receive seems to be of paramount importance. I heard from the volunteers that holding potentially emotionally charged conversations in the wake of a polarised media was no easy task.

For me, engaging with the Clive Museum at Powis Castle has been a personal journey of investigation, discovery, and self-reflection. Even though I have become more aware of many of the darker episodes of colonial history, and the difficulties that come with that, I have also gained some sense of empowerment from better understanding this part in my origin story. It is from this personal position I advocate that Powis Castle has the potential to be a space for social cohesion. Even though Powis Castle finds itself in the cross fire between what appears to be two opposing camps of the culture wars, I sense that framing the site as one of social cohesion or anti-racism can help it to step out of this dichotomy; surely no one could object to this? This is also in line with the Anti Racist Wales Action Plan which asks public bodies to fully recognise their responsibility ‘for setting the historic narrative, promoting and delivering a balanced, authentic and decolonised account of the past – one that recognises both historical injustices and the positive impact of Black Asian and Minority Ethnic communities’.

Previously, I used to think that communicating the whole story only benefitted those from marginalised communities. However, more recently I think that in giving everyone the opportunity to engage with the full colonial conversation, it can narrow some of the divisions we see in society. For those from marginalised positions, it gives a greater sense of self awareness, self esteem, belonging and potentially empowerment. For others, it offers a better understanding of how and why our society has developed in the way it has, why we all belong in society, and perhaps helps to dispel myths and misunderstanding.

I continue to reflect on what it might take for it to become a site of social healing. Even though there may have been some level of empowerment for me, inidviduals process historical events differently and I sense Powis Castle could be potentially traumatising and difficult for others, particularly those of Indian descent. I sense that those privileges and oppressions that descend from Powis Castle’s colonial links with India would need to be addressed before there can be a sincere attempt at healing.

Previously, I used to think that communicating the whole story only benefitted those from marginalised communities. However, more recently I think that in giving everyone the opportunity to engage with the full colonial conversation, it can narrow some of the divisions we see in society. For those from marginalised positions, it gives a greater sense of self awareness, self esteem, belonging and potentially empowerment. For others, it offers a better understanding of how and why our society has developed in the way it has, why we all belong in society, and perhaps helps to dispel myths and misunderstanding.

I continue to reflect on what it might take for it to become a site of social healing. Even though there may have been some level of empowerment for me, inidviduals process historical events differently and I sense Powis Castle could be potentially traumatising and difficult for others, particularly those of Indian descent. I sense that those privileges and oppressions that descend from Powis Castle’s colonial links with India would need to be addressed before there can be a sincere attempt at healing.

Do the descendants of Robert Clive owe my family reparations?

De-mystification, disentanglement and reconstruction - the search for an origin story and resolution.

Warning: this article contains an example of offensive historical language.

This has been a difficult post to write with several layers of obfuscation. Trying to figure out what has not been said, or what has been omitted, has been partly a process of investigation, but also one of deduction, personal interpretation and creative leaps.

I have woven personal family history into a narrative arc from the imperial past into the privileges and inequalities of the present. Linking disparate temporal elements together, I feel naïve not to have made some of these connections earlier.

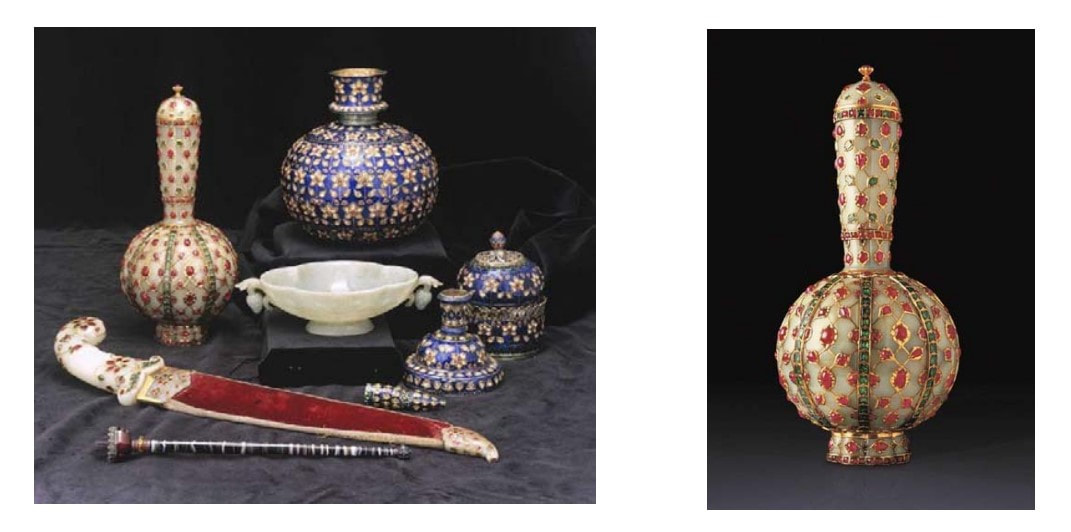

For me, the collection of South and East Asian artefacts displayed in the Clive Museum at Powis Castle is the quintessential colonial collection. It was assembled by two generations of the Clive family: Robert (who became known as Clive of India), his son Edward Clive and Henrietta Clive, wife of Edward. The National Trust acknowledge that it is not always clear whether items were purchased, received as gifts, or ‘the spoils of war’. In his book, The Anarchy, William Dalrymple describes the collection at Powis Castle as loot (1) (deriving from the Hindi word “Lut”, meaning the spoils of war). The collection is currently being re-examined with research centring on the nature in which the objects in the Clive Collection were acquired.

This has been a difficult post to write with several layers of obfuscation. Trying to figure out what has not been said, or what has been omitted, has been partly a process of investigation, but also one of deduction, personal interpretation and creative leaps.

I have woven personal family history into a narrative arc from the imperial past into the privileges and inequalities of the present. Linking disparate temporal elements together, I feel naïve not to have made some of these connections earlier.

For me, the collection of South and East Asian artefacts displayed in the Clive Museum at Powis Castle is the quintessential colonial collection. It was assembled by two generations of the Clive family: Robert (who became known as Clive of India), his son Edward Clive and Henrietta Clive, wife of Edward. The National Trust acknowledge that it is not always clear whether items were purchased, received as gifts, or ‘the spoils of war’. In his book, The Anarchy, William Dalrymple describes the collection at Powis Castle as loot (1) (deriving from the Hindi word “Lut”, meaning the spoils of war). The collection is currently being re-examined with research centring on the nature in which the objects in the Clive Collection were acquired.

The collection cannot be understood properly without contextualisation to the actions of Robert Clive in India.

Starting his career as a junior mercantile agent, Robert Clive rose to become Governor of Bengal and Commander-in-Chief of the East India Company's (EIC’s) army. Despite no formal military training Clive successfully led numerous campaigns, the most famous being the Battle of Plassey, 1757. It was also Clive who extracted territorial control for the Company as a result. For himself, he took a vast fortune in gold, silver and jewels from the treasury of the defeated Siraj ud-Daulah as spoils of war. (2)

Through Clive, the Company deployed its armies to forcibly invade and conquer the Indian subcontinent exploiting and financially profiting from the wealth and rich natural resources of India’s southern regions. This began the British Empire in India, meanwhile ensuring a fortune for Clive. (3)

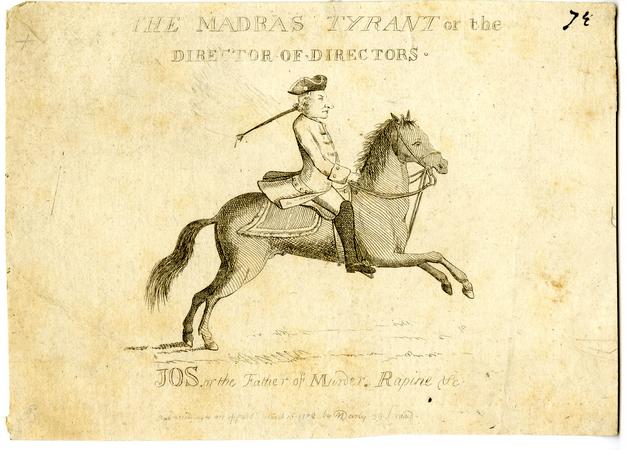

As well as being honoured, Robert Clive was also vilified in his lifetime. He earned the monikers, Madras Tyrant and Lord Vulture for his asset stripping of Bengal (4) . Robert Clive continues to be a polarising character, perhaps largely dependent on your perspective on Britain’s colonial past. Somewhat controversially there is still a statue of him outside the Foreign Office in London and more locally to Powis Castle, in Shrewsbury town centre, which has received continued calls for its removal.

Starting his career as a junior mercantile agent, Robert Clive rose to become Governor of Bengal and Commander-in-Chief of the East India Company's (EIC’s) army. Despite no formal military training Clive successfully led numerous campaigns, the most famous being the Battle of Plassey, 1757. It was also Clive who extracted territorial control for the Company as a result. For himself, he took a vast fortune in gold, silver and jewels from the treasury of the defeated Siraj ud-Daulah as spoils of war. (2)

Through Clive, the Company deployed its armies to forcibly invade and conquer the Indian subcontinent exploiting and financially profiting from the wealth and rich natural resources of India’s southern regions. This began the British Empire in India, meanwhile ensuring a fortune for Clive. (3)

As well as being honoured, Robert Clive was also vilified in his lifetime. He earned the monikers, Madras Tyrant and Lord Vulture for his asset stripping of Bengal (4) . Robert Clive continues to be a polarising character, perhaps largely dependent on your perspective on Britain’s colonial past. Somewhat controversially there is still a statue of him outside the Foreign Office in London and more locally to Powis Castle, in Shrewsbury town centre, which has received continued calls for its removal.

These are some of the more significant personal outcomes for Robert Clive that resulted from his actions in India.

• He became one of the richest men in Europe. Following the Battle of Plassey in 1757, Clive was appointed Governor of Bengal, and received the equivalent of £234,000 (£23 million today) in cash instantly making him one of the richest self-made men in Europe.5

• He was ennobled as the 1st Baron Clive of Plassey in the County of Clare, in the Peerage of Ireland. He was subsequently knighted in 1764.

• He expended large sums of cash to ensure a seat in Parliament6. He became MP for Shrewsbury in 1761 until his death.

• He paved the way for his son Edward Clive to marry into the Britsh nobility. Edward married Lady Henrietta Herbert, daughter of the 1st Earl of Powis, in 1784. Essentially, the groom was able to pay of the considerable debts of the Herberts and Powis castle, and ultimately inherited the title Earl of Powis after it became extinct on the death of his brother-in-law.

• Throughout his life Robert Clive struggled with mental health and ultimately took his own life aged 49. Following his death, the writer Samuel Johnson wrote that he ‘had acquired his fortune by such crimes that his consciousness of them impelled him to cut his own throat’.

Through his role in the East India Company, Robert Clive was one of the key individuals involved in the early subjugation of India by the British. Although he may or may not have been the architect, he certainly was a key protagonist that paved the way for the formal colonisation of India by the British state in 1858. Therefore, to my mind, not only does Robert Clive bear responsibility for what happened during his tenure at the EIC, but also in some part for what subsequently followed under the mechanics of Empire.

We know huge sums of money were extracted under Empire. In 1600, when the East India Company was founded, Britain was generating 1.8% of the world’s GDP, while India was producing 22.5%. By the peak of the Raj, those figures had more or less been reversed: India was reduced from the world’s leading manufacturing nation to a symbol of famine and deprivation (7).

• He became one of the richest men in Europe. Following the Battle of Plassey in 1757, Clive was appointed Governor of Bengal, and received the equivalent of £234,000 (£23 million today) in cash instantly making him one of the richest self-made men in Europe.5

• He was ennobled as the 1st Baron Clive of Plassey in the County of Clare, in the Peerage of Ireland. He was subsequently knighted in 1764.

• He expended large sums of cash to ensure a seat in Parliament6. He became MP for Shrewsbury in 1761 until his death.

• He paved the way for his son Edward Clive to marry into the Britsh nobility. Edward married Lady Henrietta Herbert, daughter of the 1st Earl of Powis, in 1784. Essentially, the groom was able to pay of the considerable debts of the Herberts and Powis castle, and ultimately inherited the title Earl of Powis after it became extinct on the death of his brother-in-law.

• Throughout his life Robert Clive struggled with mental health and ultimately took his own life aged 49. Following his death, the writer Samuel Johnson wrote that he ‘had acquired his fortune by such crimes that his consciousness of them impelled him to cut his own throat’.

Through his role in the East India Company, Robert Clive was one of the key individuals involved in the early subjugation of India by the British. Although he may or may not have been the architect, he certainly was a key protagonist that paved the way for the formal colonisation of India by the British state in 1858. Therefore, to my mind, not only does Robert Clive bear responsibility for what happened during his tenure at the EIC, but also in some part for what subsequently followed under the mechanics of Empire.

We know huge sums of money were extracted under Empire. In 1600, when the East India Company was founded, Britain was generating 1.8% of the world’s GDP, while India was producing 22.5%. By the peak of the Raj, those figures had more or less been reversed: India was reduced from the world’s leading manufacturing nation to a symbol of famine and deprivation (7).

The process of extraction extended from goods to labour. Following the abolition of transatlantic slavery, Britain struggled to find a labour force to replace the former enslaved Africans across its empire. Following various failed attempts to find replacement workers, the powerful plantocracy lobbied the government for help. Sugar plantation owner John Gladstone (father of later Prime Minister William Gladstone) wrote to the Colonial Secretary and was anxious to obtain ‘a supply of Hill Coolies from Bengal’ to be imported as indentured labourers.8 Subsequently, Gladstone was promptly granted permission by Order in Council to recruit indentured labourers from his agent in India.

My 91 year old Guyanese grandfather proudly refers to himself as a ‘coolie’. The now pejorative term was used to refer to Indian indentured labourers (unskilled workers) in the 18th century. It was his ancestors that would have been transported from India to British Guiana under the indentureship system. The hardship of indentureship is perhaps hard to imagine.

My 91 year old Guyanese grandfather proudly refers to himself as a ‘coolie’. The now pejorative term was used to refer to Indian indentured labourers (unskilled workers) in the 18th century. It was his ancestors that would have been transported from India to British Guiana under the indentureship system. The hardship of indentureship is perhaps hard to imagine.

With few exceptions the workers were treated with great severity. Their accommodation was either too confined or disgustingly filthy, or none was provided for them, and in cases of sickness there was the most culpable neglect. Life on the estates was hard and miserable. They lived in the old slave barracks the nigger yards, in little rooms with no privacy or cooking facilities. They had to use the bush for latrines. Water supplies were often polluted, and the food was dull and below standard. (9)

On visiting the Clive Museum at Powis Castle I had wrongly assumed that the all of the contents were owned by the National Trust. It transpires that at least some of the collection is owned by the current Earl of Powis along with many of the other items that fill Powis Castle. For clarity, the current Earl of Powis, John Herbert is a direct descendent of Robert Clive, as elucidated on the backpage of the National Trust’s Powis Castle guidebook. Among others, John Herbert inherited the title Baron Clive of Plassey, alluding to one of Robert Clive’s most decisive victories in India against the last independent Nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud Daulah.

There are numerous privileges that have passed down through generations from Robert and Edward Clive to the current earl; the Powis estate and inherited artefacts being just some of them. By contrast, what is the legacy for the descendants of; colonised people (my paternal family), indentured workers (my maternal family), and the numerous victims of imperial ambitions. Where is their privilege?

In 2004, descendants of Robert Clive put 5 items from the Clive Collection up for auction at Christie’s. These items, once part of the royal collection at the Imperial Court in Delhi, comprising a jade bottle flask, dagger, jade bowl, agate fly whisk and huqqa set realised a sale price £4.1m for the family. This is not an isolated example, more recently Robert Clive’s silver Durbar set was sold.

There are numerous privileges that have passed down through generations from Robert and Edward Clive to the current earl; the Powis estate and inherited artefacts being just some of them. By contrast, what is the legacy for the descendants of; colonised people (my paternal family), indentured workers (my maternal family), and the numerous victims of imperial ambitions. Where is their privilege?

In 2004, descendants of Robert Clive put 5 items from the Clive Collection up for auction at Christie’s. These items, once part of the royal collection at the Imperial Court in Delhi, comprising a jade bottle flask, dagger, jade bowl, agate fly whisk and huqqa set realised a sale price £4.1m for the family. This is not an isolated example, more recently Robert Clive’s silver Durbar set was sold.

The current Earl of Powis has stated he is an anti-imperialist (10). But what does this mean in practice, especially when you are still a direct beneficiary of empire in multiple ways. In line with many prevailing debates, might I suggest some form of reparation or restorative justice. To be anti-imperialist is surely a verb and not just a noun. For me, reparations are not necessarily about financial compensation but are about acknowledgement, truth telling and apology. I sense it is also taking an active role in helping to reduce the inequalities that still exist as a result of the historical injustices of empire. The Earl of Powis may well be involved in these activities, however I could find little evidence to support this online.

It can often be difficult to unravel the complexities of empire and its lasting impact. However at Powis Castle, some of those privileges of Empire are writ large. I sense that the Herbert family have perhaps been able to avoid direct calls for reparations sitting behind the veil of the National Trust; a trusted household name that looks after ‘nature, beauty and history for everyone, forever’. I’m curious to know the details of the arrangement and relationship between the National Trust and the Herbert Family. Despite the National Trust’s positive work on its Colonialism and historic slavery report, I wonder if that relationship re-inforces any privileges of empire?

I’m also curious to know who owns what within Powis Castle and also within the Clive Collection. This is perhaps one of those layers of obfuscation that I referred to earlier.

In a recent Guardian article (11), it suggested that the debate around reparations and restorative justice in relation to slavery and colonialism are likely to intensify. Perhaps the Earl of Powis and the other descendants of Robert Clive might should enter into a constructive dialogue to establish what form these reparations or restorative justice might take.

The optimist in me senses a corner is being turned slowly but surely, and I am reminded of the following quote ‘the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.’

1. Dalrymple, W (2020) Anarchy, The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. Bloomsbury.

2. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/discover/history/what-was-the-east-india-company

3. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/wales/powis-castle-and-garden/the-clive-museum-collection-at-powis-castle

4. Robert Clive was a vicious asset-stripper. His statue has no place on Whitehall | William Dalrymple | The Guardian

5. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/04/east-india-company-original-corporate-raiders

6. https://juliaherdman.com/?s=robert+clive

7. https://www.theguardia8n.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/11/robert-clive-statue-whitehall-british-imperial

8. https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a-new-system-of-slavery-the-british-west-indies-and-the-origins-of-indian-indenture/

9. Mukesh Kumar, Malaria and mortality among indentured indians: a study of housing, sanitation, and health in british guiana (1900-1939), Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 74 (2013), pp. 746-757

10. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/nov/19/clive-of-india-statue-in-shrewsbury-should-be-removed-says-descendant-channel-4

11. More than money: the logic of slavery reparations | Slavery | The Guardian

NB. Increasingly I am calling into question some of the assertions and conclusions made by William Dalrymple.

2. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/discover/history/what-was-the-east-india-company

3. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/wales/powis-castle-and-garden/the-clive-museum-collection-at-powis-castle

4. Robert Clive was a vicious asset-stripper. His statue has no place on Whitehall | William Dalrymple | The Guardian

5. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/04/east-india-company-original-corporate-raiders

6. https://juliaherdman.com/?s=robert+clive

7. https://www.theguardia8n.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/11/robert-clive-statue-whitehall-british-imperial

8. https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a-new-system-of-slavery-the-british-west-indies-and-the-origins-of-indian-indenture/

9. Mukesh Kumar, Malaria and mortality among indentured indians: a study of housing, sanitation, and health in british guiana (1900-1939), Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 74 (2013), pp. 746-757

10. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/nov/19/clive-of-india-statue-in-shrewsbury-should-be-removed-says-descendant-channel-4

11. More than money: the logic of slavery reparations | Slavery | The Guardian

NB. Increasingly I am calling into question some of the assertions and conclusions made by William Dalrymple.

On seeing a tiger skin at Powis Castle

I was totally unaware of the Clive Museum at Powis Castle until I attended a series of seminars at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery. Amassed during the British colonisation of India, ‘the collection of artefacts from India displayed in the Clive Museum is the largest private collection of this type in the UK’. ‘The museum includes ivories, textiles, statues of Hindu gods, ornamental silver and gold, weapons and ceremonial armour’. However, on visiting Powis Castle it was the tiger skin hanging high up on a wall that drew my immediate attention. For me, I find the display of tiger skins to be highly problematic; they are an anachronism, an uncomfortable relic of a bygone era.

On seeing the tiger skin at Powis Castle, I was immediately caught by the awkward articulation of the full taxidermied head against the flattened and flayed body. Perhaps the most unnerving element was the fully alert glass eyes that sat in contrast to the dead body. Without any meaningful interpretation on display, I felt that this apex predator had simply been relegated to a decorative object.

But what else does this tiger skin represent?

On seeing the tiger skin at Powis Castle, I was immediately caught by the awkward articulation of the full taxidermied head against the flattened and flayed body. Perhaps the most unnerving element was the fully alert glass eyes that sat in contrast to the dead body. Without any meaningful interpretation on display, I felt that this apex predator had simply been relegated to a decorative object.

But what else does this tiger skin represent?

Perhaps the easiest and most obvious answer would be the preservation of a kill, or a mere hunting trophy. If this is the case - I’m curious to know who killed this particular animal, and in what circumstances; perhaps the castle have this information on record.

Another insight is given in a book published in association with the National Trust called Treasures from India: The Clive Collection at Powis Castle (1987). In the chapter entitled The British as Collectors and Patrons in India, it explains that ‘collecting’ was regarded as a highly serious activity in 16th and 17th century Europe; an essential part of a learned and cultivated life. Ostensibly, it was an intellectual attempt to understand the nature of the universe by assembling ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ objects, a model of universal nature made private.

For me the tiger skin takes on a greater meaning when considered within the context of the colonial collection at Powis Castle. The Clive Museum is named after two generations of the Clive family.

For those who may be unaware (or like me were not taught colonial history at school), Robert Clive was a key figure in the East India Company (EIC). Primarily through force, the EIC financially profited from the wealth and natural resources of India and ultimately laid the foundation for the formal colonisation of India by the British in 1858.

The following journal entry offers a potential reading of the tiger skin within a colonial context. In 1864, the British Army Officer Walter Campbell wrote ‘Never attack a tiger on foot—if you can help it. There are cases in which you must do so. Then face him like a Briton, and kill him if you can; for if you fail to kill him, he will certainly kill you’. By mimicking the exploits of Mughal emperors, the British were seeking to position themselves as the new Mughals. Tigers represented for the British all that was wild and untamed in the Indian natural world. Sramek (2006) postulates ‘Precisely because tigers were dangerous and powerful beasts, tiger hunting represented a struggle with fearsome nature that needed to be resolutely faced "like a Briton," as Campbell put it. Only by successfully vanquishing tigers would Britons prove their manliness and their fitness to rule over Indians’.

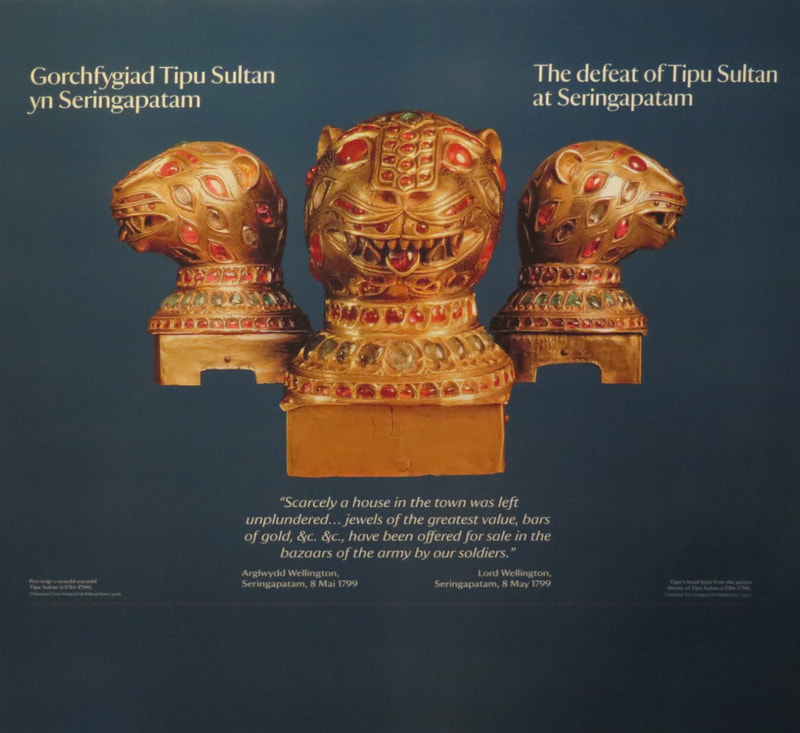

One of the greatest adversaries of British rule in India was Tipu Sultan whose personal emblem was the tiger. Many of Tipu’s personal possessions are decorated with a tiger motif, including one of the finials from his throne which can be found within the Clive Museum (there is another one in the V&A museum in London).

Symbolically, does the tiger skin at Powis Castle represent the defeat of a key enemy, the defeat of a nation, and a fitness to rule over Indians?

Another insight is given in a book published in association with the National Trust called Treasures from India: The Clive Collection at Powis Castle (1987). In the chapter entitled The British as Collectors and Patrons in India, it explains that ‘collecting’ was regarded as a highly serious activity in 16th and 17th century Europe; an essential part of a learned and cultivated life. Ostensibly, it was an intellectual attempt to understand the nature of the universe by assembling ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ objects, a model of universal nature made private.

For me the tiger skin takes on a greater meaning when considered within the context of the colonial collection at Powis Castle. The Clive Museum is named after two generations of the Clive family.

For those who may be unaware (or like me were not taught colonial history at school), Robert Clive was a key figure in the East India Company (EIC). Primarily through force, the EIC financially profited from the wealth and natural resources of India and ultimately laid the foundation for the formal colonisation of India by the British in 1858.

The following journal entry offers a potential reading of the tiger skin within a colonial context. In 1864, the British Army Officer Walter Campbell wrote ‘Never attack a tiger on foot—if you can help it. There are cases in which you must do so. Then face him like a Briton, and kill him if you can; for if you fail to kill him, he will certainly kill you’. By mimicking the exploits of Mughal emperors, the British were seeking to position themselves as the new Mughals. Tigers represented for the British all that was wild and untamed in the Indian natural world. Sramek (2006) postulates ‘Precisely because tigers were dangerous and powerful beasts, tiger hunting represented a struggle with fearsome nature that needed to be resolutely faced "like a Briton," as Campbell put it. Only by successfully vanquishing tigers would Britons prove their manliness and their fitness to rule over Indians’.

One of the greatest adversaries of British rule in India was Tipu Sultan whose personal emblem was the tiger. Many of Tipu’s personal possessions are decorated with a tiger motif, including one of the finials from his throne which can be found within the Clive Museum (there is another one in the V&A museum in London).

Symbolically, does the tiger skin at Powis Castle represent the defeat of a key enemy, the defeat of a nation, and a fitness to rule over Indians?

My final reading of the tiger skin is both an economic and ecological one.

During the colonial period there was a commonly held belief that colonisation was primarily a civilising mission - The White Man’s Burden. This was essentially a pretence for what was first and foremost a process of extraction. For me, the following statistic starkly reinforces this fact: at the start of the 18th century India’s share of the world economy was 23%, when Britain left in 1947 it was around 3% (Tharoor 2017).

Under colonisation, British planters forced Indian famers to grow commercial crops on their land, such as tea, poppies (for opium production) and indigo. Cultivation on the scale required to make significant profits required the clearing of wild habitats for agricultural use. Tigers were an animal to be eradicated in order to extend agricultural land. Although tiger hunting began as a sport, it switched to become an economic imperative under colonial rule.

To intensify activity the British declared tigers (as well as lions, cheetahs and leopards) as vermin and offered a bounty for every predator killed. According to one popular estimation, 80,000 tigers were killed between 1875 and 1925 and were nearly hunted to extinction under British colonial rule. According to the last census in 2018, there are only 2967 tigers living in India today.

The exact cost of historic habitat destruction, bio-diversity loss and the introduction of invasive species to India under colonial rule is perhaps impossible to calculate. I feel that the environmental damage caused under colonialism is often overlooked, even though it is readily visible within colonial collections.

As a person of Indian descent living within Wales, my reading of the tiger skin hanging at Powis Castle is likely to differ to others. Within the context of the Clive Museum at Powis Castle, for me, the tiger skin represents a domination over nature, Indians and Otherness - the ramifications of which continue to play out economically, culturally and environmentally to this day.

What does it mean to approach this work as a Welsh artist?

I was asked what does it mean to approach this work as a Welsh artist? This seemed like a curious question to me so I wanted to unravel it a little. I struggle somewhat with the limitations of tying myself to a particular nationality, but for the sake of this post lets just say that I am a Welsh artist of Indian descent.

I moved to Wales shortly after devolution. Although I wasn't involved in the arts at that time, looking back at some key publications (Certain Welsh artists, Here + Now, Imaging Wales) it seems many artists in Wales at the time were addressing concerns relating to politics, language, post-industrialisation, mythology and the land. There seemed to be a general redefining of the Welsh identity, as distinct from a wider British identity. If Wales was England's first colony (as suggested in Imaging Wales) it could perhaps be said that many of the artists at the time were involved in a process of cultural decolonisation.

The following quote by Gwyn A William comes to mind - The Welsh as a people have lived by making and remaking themselves in generation after generation, usually against the odds, usually within a British context. Wales is an artefact which the Welsh produce. If they want to. It requires an act of choice.

However, looking back at these publications, I get a sense that certain artist voices were minoritised (although I'm happy to be proved wrong). Where were the Black, Asian and other ethnically diverse artist voices of Wales? I wonder if these minoritised voices essentially represented the colonised voice within the colonised, and were therefore at a double remove from the table. Perhaps the environment wasn't fertile enough for those voices to emerge, or, that the re-assertion of a unique Welsh identity was too narrow at the time.

On a more progressive note, I sense the environment has changed. I feel that books like Welsh Plural (Essays on the Future of Wales) are helping to carve and shape the identity of a far more pluralistic and inclusive Wales than previously envisioned. I also think intersectionality as a framework offers an opportunity to think about how oppressions are linked, and are not necessarily in conflict with each other. Although I may still represent a marginalised voice, I sense a change in the environment, that people are more receptive to the conversation I want to explore. In part, I think there is a contextual understanding because of Wales' historic relationship to England and what it might mean to have your cultural history misrepresented or erased.

I moved to Wales shortly after devolution. Although I wasn't involved in the arts at that time, looking back at some key publications (Certain Welsh artists, Here + Now, Imaging Wales) it seems many artists in Wales at the time were addressing concerns relating to politics, language, post-industrialisation, mythology and the land. There seemed to be a general redefining of the Welsh identity, as distinct from a wider British identity. If Wales was England's first colony (as suggested in Imaging Wales) it could perhaps be said that many of the artists at the time were involved in a process of cultural decolonisation.

The following quote by Gwyn A William comes to mind - The Welsh as a people have lived by making and remaking themselves in generation after generation, usually against the odds, usually within a British context. Wales is an artefact which the Welsh produce. If they want to. It requires an act of choice.

However, looking back at these publications, I get a sense that certain artist voices were minoritised (although I'm happy to be proved wrong). Where were the Black, Asian and other ethnically diverse artist voices of Wales? I wonder if these minoritised voices essentially represented the colonised voice within the colonised, and were therefore at a double remove from the table. Perhaps the environment wasn't fertile enough for those voices to emerge, or, that the re-assertion of a unique Welsh identity was too narrow at the time.

On a more progressive note, I sense the environment has changed. I feel that books like Welsh Plural (Essays on the Future of Wales) are helping to carve and shape the identity of a far more pluralistic and inclusive Wales than previously envisioned. I also think intersectionality as a framework offers an opportunity to think about how oppressions are linked, and are not necessarily in conflict with each other. Although I may still represent a marginalised voice, I sense a change in the environment, that people are more receptive to the conversation I want to explore. In part, I think there is a contextual understanding because of Wales' historic relationship to England and what it might mean to have your cultural history misrepresented or erased.

A re-writing of The Tiger who Came to Tea

This was one of my favourite books when I was young. However, on a recent re-reading of it I couldn't help but think that the tiger in the story stands in for a somewhat exotic 'outsider'. Somehow I managed to relate to the tiger, perhaps because I imagine it to be an Indian tiger - and I do have a big appetite. But in the story the tiger never comes back - and we never find out why. Essentially he is the 'bad immigrant' lol. breaking all the customs, eating all the food and never returning. Somehow, I was prompted to re-write the text from the tigers point of view to explain why he never returns.

Tea at Sophie’s house

It was a strange set of circumstances that bought me to this place, but the people in this place were perhaps stranger still and stories of their peculiarities could fill the many pages of a book.

But I would like to tell you the story of one particular afternoon.

A certain house drew my attention. The front door was painted red. Don’t you know, all the best houses have red doors.

I extended my paw and pressed the bell.

At that moment I wondered who might live inside that house, with its red painted door.

Perhaps a friendly old woman,

or a young couple in love,

or maybe a family with many wild and rambunctious children.

I didn’t have to wait long to find out.

As the door opened a wonderful smell of food drifted through the air and reached my tender tiger nostrils.

I was reminded of how hungry I was.

It was a polite young girl who had opened the door, wearing a purple dress with a blue ribbon in her hair.

‘Hello, my name’s Sophie’ she said

‘Excuse me, I’m very hungry, do you think I could have tea with you?’ I replied

Sophie’s mummy said

‘Of course, come in’.

I made my way into the house. The house was very small and my head nearly touched the ceiling.

I sat down at the table where Sophie and her mummy were having tea.

Sophie’s mummy said to me ‘Would you like a sandwich?’

I’d never eaten a sandwich before. Nor had I eaten food in the shape of triangle.

But they looked delicious. I was so hungry I swallowed them all in one big mouthful.

Owp!

I was still hungry and luckily Sophie passed me the buns.

I ate the first bun, it was sticky but delicious. I then decided to eat all of the buns, and then I ate all of the biscuits, and then all of the cake – until there was no food left on the table.

Sophie’s mummy then said

‘Would you like a drink?’

She handed me this peculiar little cup. It was too small and dainty for my big furry paws.

This simply wouldn’t do. I had no choice but to drink all of milk in the milk jug and all of the tea in the teapot.

I was still quite hungry, and Sophie and I hunted around the kitchen for something else to eat.

There was some wonderful supper cooking in the saucepans on the stove – which I decided to eat.

I then ate all of the food in the fridge.

And then all of the packets and the tins in the cupboard.

I then drank all the milk,

All of the orange juice,

All of Daddy’s beer

And … all the water in the tap.

Not wishing to out stay my welcome, or to forget my manners

I said ‘ thank you for my nice tea, I think I’d better go now’.

If only all the people in this strange place were as wonderful as Sophie and her mummy I might have decided to stay.

But with trumpet in hand, I decided to move on.

It was a strange set of circumstances that bought me to this place, but the people in this place were perhaps stranger still and stories of their peculiarities could fill the many pages of a book.

But I would like to tell you the story of one particular afternoon.

A certain house drew my attention. The front door was painted red. Don’t you know, all the best houses have red doors.

I extended my paw and pressed the bell.

At that moment I wondered who might live inside that house, with its red painted door.

Perhaps a friendly old woman,

or a young couple in love,

or maybe a family with many wild and rambunctious children.

I didn’t have to wait long to find out.

As the door opened a wonderful smell of food drifted through the air and reached my tender tiger nostrils.

I was reminded of how hungry I was.

It was a polite young girl who had opened the door, wearing a purple dress with a blue ribbon in her hair.

‘Hello, my name’s Sophie’ she said

‘Excuse me, I’m very hungry, do you think I could have tea with you?’ I replied

Sophie’s mummy said

‘Of course, come in’.

I made my way into the house. The house was very small and my head nearly touched the ceiling.

I sat down at the table where Sophie and her mummy were having tea.

Sophie’s mummy said to me ‘Would you like a sandwich?’

I’d never eaten a sandwich before. Nor had I eaten food in the shape of triangle.

But they looked delicious. I was so hungry I swallowed them all in one big mouthful.

Owp!

I was still hungry and luckily Sophie passed me the buns.

I ate the first bun, it was sticky but delicious. I then decided to eat all of the buns, and then I ate all of the biscuits, and then all of the cake – until there was no food left on the table.

Sophie’s mummy then said

‘Would you like a drink?’

She handed me this peculiar little cup. It was too small and dainty for my big furry paws.

This simply wouldn’t do. I had no choice but to drink all of milk in the milk jug and all of the tea in the teapot.

I was still quite hungry, and Sophie and I hunted around the kitchen for something else to eat.

There was some wonderful supper cooking in the saucepans on the stove – which I decided to eat.

I then ate all of the food in the fridge.

And then all of the packets and the tins in the cupboard.

I then drank all the milk,

All of the orange juice,

All of Daddy’s beer

And … all the water in the tap.

Not wishing to out stay my welcome, or to forget my manners

I said ‘ thank you for my nice tea, I think I’d better go now’.

If only all the people in this strange place were as wonderful as Sophie and her mummy I might have decided to stay.

But with trumpet in hand, I decided to move on.

Partnership with Artes Mundi and the National Trust

I'm happy to say I will be working in partnership with Artes Mundi and the National Trust to explore the South Asian collection at Powis Castle. The partnership will consist of a period of research culminating in a series of works, including an on-site performance in Summer 2023.

The proposed title for the performance A Tiger in the Castle hence the name for the blog page.

This page will articulate some of my research and thinking.

The proposed title for the performance A Tiger in the Castle hence the name for the blog page.

This page will articulate some of my research and thinking.

Links to other work relating to Powis Castle

Nisha Duggal

(993) Artist Talk: Nisha Duggal - YouTube

NISHA DUGGAL - In a Welsh castle, boxed treasures from home /...

Hassan Vawda

https://www.roots-routes.org/%D8%AC%D8%A7-%D9%85%D9%90is-wineglass-the-national-trusts-powis-castle-and-the-clive-of-india-collection-by-hassan-vawda/

(993) Artist Talk: Nisha Duggal - YouTube

NISHA DUGGAL - In a Welsh castle, boxed treasures from home /...

Hassan Vawda

https://www.roots-routes.org/%D8%AC%D8%A7-%D9%85%D9%90is-wineglass-the-national-trusts-powis-castle-and-the-clive-of-india-collection-by-hassan-vawda/