From Guyana to England

My mum moved from Guyana to England in 1963 when she was 11 years-old. I spoke to her about this experience in her garden - a place where her creativity flourishes - her pride and joy. I also took inspiration from Alice Walker's text in Search of our Mothers' Gardens suggested to me by fellow artist, Jade Montserrat.

7 Things I Unlearned at Art School

Not all educational experiences are equal. The negative ones can scar you, but the positive ones have the ability to transform you. I was lucky enough to go to university twice, first to study Geology at Imperial College and secondly Fine Art at Swansea College of Art.

As a mature student going to Art School, I thought my life experiences might give me a certain edge, but it turns out that it was quite the opposite. As I was to find out, the knowledge I had gained through formal education was built on some fairly insecure foundations.

For most of my education I had been a passive recipient of knowledge and not the constructor of it. It seems I had to dig down and repair the foundations before I could rebuild. Before I could learn, I had to unlearn.

What follows are some of the unlearning episodes that I experienced at Art School.

1.Possibilities, not answers

Throughout my school education I was taught that there are right and wrong answers. Even when there appeared to be room for interpretation on an exam paper, there was still clearly the right interpretation or the wrong one. At Art School I was taught to dismiss these two positions from the outset. For example, it is simply incorrect to say there is a right interpretation of a piece of art and a wrong one; instead, subjectivity reigns supreme. Art is at its most comfortable when there is a lack of resolution. It seeks possibilities, not answers or clarification.

2.Deconstructing the binaries

An education system built on right and wrong answers might explain a prevalence of binary thinking in my adult life. This binary thinking is reinforced by the media which seems to polarise complex arguments; Brexit is a case in point - you either wanted in or out.

Simple categories are constructed 'on our behalf' whether we like it or not. Immigration is another example. We are often asked to choose between us and them; but who is ‘us’ and what exactly do we mean by ‘them’? The conversation becomes a little more uncomfortable when you realise, that depending on the conversation, you might fall into the ‘them’ category.

Art School encourages us to interrogate these categories which are often the constructs of power. Once these boundaries are deconstructed, new fertile ground for thinking and operating emerges. Rather than positioning ourselves on one side of the debate or the other, it is possible to occupy new positions previously unthought of.

3.Removing the lenses

The way I view the world is a cumulation of the formative processes in which my background plays a significant part. My gender, race, religion, class and parental upbringing all have a bearing on my thought processes. Art School teaches us to identify or at least acknowledge the lenses through which we see the world and consider their validity. Through considering these lenses our perspective can often shift and we are open to new possibilities of seeing the world.

4.Alternative histories

The scaffolding that we learn in our formal history education seems to be the logical place to assimilate new information, but what happens if this scaffolding is fundamentally incorrect and needs to be rebuilt? The old adage ‘history is written by the victors’ seems to hold sway, with the western version of history being typically an imperial one. Art School teaches us to pay attention to alternative histories, to those of marginalised groups; to the victims rather than the victors; and to those who seem to fall outside the norm. Rather than a futile exercise in revisionism, such an exercise opens up new ways of contextualising the present and potential ways to re-boot the future.

5.Question the question

As an adult we are required to answer questions that come to us in a variety of official formats; typically we dutifully conform. The questions we are asked are rarely neutral and are often posed from a specific position or perspective. Often the design of these questions generates a limited set of answers; this is useful for the quantitative data analysers but does not give the whole picture. Art School teaches us to think about who is asking these questions and how they are phrased. Are the questions appropriate ones to be asked, and should we be answering them so obligingly?

6.Trampling across disciplines

I was educated to believe that progression in a given subject involved studying it at a deeper level. Any subject can be broken down into specialisms, and then even further into micro-specialisms; this seems to be where the majority of research takes place. However, these rarefied niches are not the only place where knowledge can be constructed. Art School encourages us travel sideways across disciplines; to find their natural intersections or better still to create new ones. By connecting what may appear to be extraneous fields of knowledge, new solutions, conversations and possibilities emerge.

7.It is not all about the outcome

In formal education it is the end result or product that is celebrated, this often drives processes and behaviours. Thinking back to my education - I was taught to the test and how to pass exams (memories of practice papers and rehearsed answers). By contrast, Art School places as much value on the ‘process’ as it does on any final product or outcome. An artist learns to value the process from which any number of given outcomes or possibilities may subsequently emerge.

I'm incredibly grateful to all of the lecturers who taught me and would like to thank them, including Tim Davies, Craig Wood, Sue Williams and Harold Hope.

Honours and the arts

In 1919, the Indian poet and polymath Rabindranath Tagore returned his knighthood to the British crown following the tragedy at Amritsar during which British military personnel shot unarmed civilians. The official death count was 379, however this number is heavily contested and could be as much as 1000.

Tagore wanted to distance himself from the British Empire under whose name this tragedy had occurred.

The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part, wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those countrymen who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings. - Rabindranath Tagore

Over recent years the rate of people declining honours or returning them has steadily increased. The personal reasons given by individuals for declining and returning honours varies widely.

I can only imagine how difficult it must be for a Black or Asian person to accept an honour given their explicit relationship to empire e.g. CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire), OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) and MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire). It must be bittersweet knowing you have earned your place at the table but aware that it is still tainted by the remnants of empire.

Tagore wanted to distance himself from the British Empire under whose name this tragedy had occurred.

The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part, wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those countrymen who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings. - Rabindranath Tagore

Over recent years the rate of people declining honours or returning them has steadily increased. The personal reasons given by individuals for declining and returning honours varies widely.

I can only imagine how difficult it must be for a Black or Asian person to accept an honour given their explicit relationship to empire e.g. CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire), OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) and MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire). It must be bittersweet knowing you have earned your place at the table but aware that it is still tainted by the remnants of empire.

|

Perhaps one of the most public rejections I can remember was by the poet Benjamin Zephaniah who stated ‘I get angry when I hear that word "empire"; it reminds me of slavery, it reminds of thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers brutalised’.

But what about white people? In an age of allyship in line with the Black Lives Matter movement should they too be thinking twice about accepting honours. The honours system represents the greatest level of public recognition one can receive in the arts in Wales. However, it is also widely acknowledged that the arts in Wales is not as diverse and inclusive as it should be, with arts organisations working towards greater levels of inclusivity. So, here’s the rub; how do you encourage diversity on a ground level when public recognition at the top of the arts is synonymous with a relationship to empire? Perhaps a different recognition system is needed or maybe there needs to be whole scale overhaul of the current honours system - I certainly wouldn’t be the first person to advocate for this. It may feel that I am making an argument that is rooted in history, however the legacy of empire still looms large especially in those countries that were colonised. Even in Britain, the negative effects of Empire is not too difficult to find. At the time of writing there are still members of the Windrush generation who are waiting to receive compensation from the British government having been wrongly deported or denied the opportunity to work. |

I certainly do not hold it against anyone that may have accepted an honours, after all they have been clearly earned. However, I can’t help but feel deep respect for those who declined or returned their honours based on moral conscience.

..

For a historical perspective of empire could I suggest Shashi Tharoor’s book, Inglorious Empire: What the British did to India.

..

For a historical perspective of empire could I suggest Shashi Tharoor’s book, Inglorious Empire: What the British did to India.

Review of Undo Things Done

|

Contemporary artists have always sought to use the most appropriate materials for their concepts. Ever since Marcel Duchamp proposed that a urinal could be a piece of art, not only was the readymade legitimised but he also opened up further conversations relating to the use of materials within art. In fact, whole movements have been centred around the use of particular materials; Arte Povera is an example with their emphasis on the use of commonplace materials such as earth, rock, paper, clothes and rope. Authenticity matters when it comes to materials and concepts; striking a balance between the two is perhaps the real challenge of artists.

The selected title for the 58thVenice Biennale exhibition is May You Live in Interesting Times. Such a title evokes a sense of challenge for the selected artists to go beyond simplification in order to represent the complexity of our times. As expected, many artists have chosen to tackle major contemporary concerns; such as, climate change, migration and fake news. Notably, other conversations have fallen off the table, with feminism seemingly taking a back seat this time. This year the artist chosen to represent Wales in Venice was Sean Edwards. |

|

Sean Edwards proposition for Wales in Venice is an autobiographical one and takes as its starting point the artist’s experience of growing up on a council estate in Cardiff in the 1980’s. There is an inherent danger is presenting autobiographical work which can often appear self-indulgent on the part of the artist; this was an accusation levelled at Tracey Emin in the early days. However, what quickly becomes apparent in Edwards’ work is that it opens up wider conversations related to class and social mobility. In the artists own words he is interested in capturing and translating the notion of growing up ‘not expecting much’.

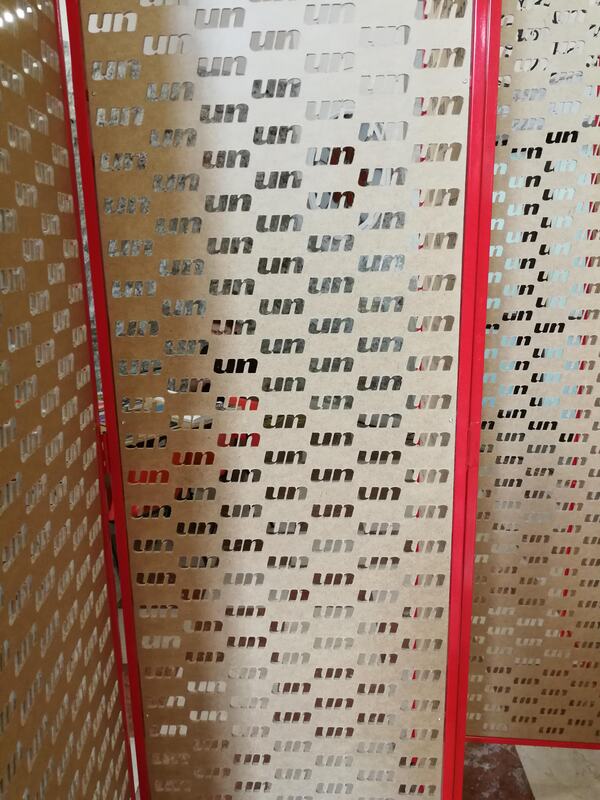

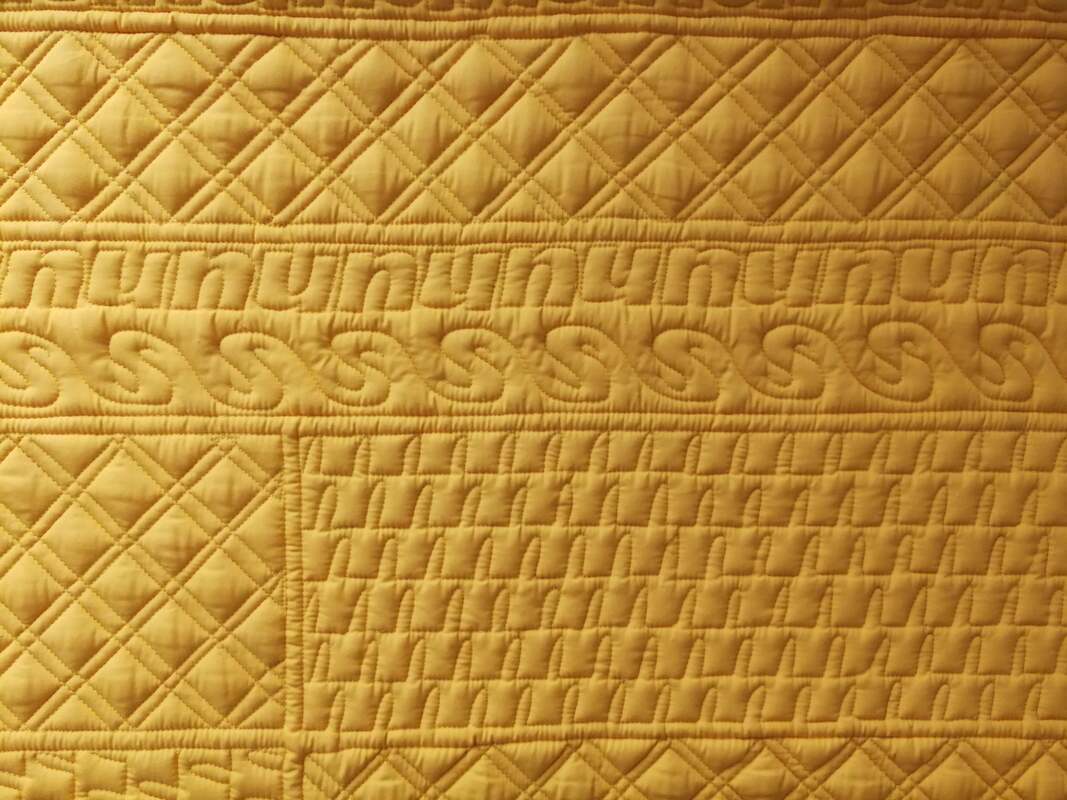

Edwards takes a number of approaches in translating his experience into language. The font from the masthead of The Sun newspaper can be found in a number of works, including his whole cloth quilts and ‘confessional’ MDF screens. The Sunwas banned in his household as a child with the left leaning Daily Mirrorbeing the newspaper of choice. During his studies in London, Edwards bought The Sun as an illicit daily ritual in order to inform his practice. We learn from interviews that Edwards attributes The Sun with having many negative influences on society. |

|

Click Using the aforementioned font, Edward exhibits a poster that simply says ‘Free School Dinners’; this is a reference to his experience at school where those entitled to free school meals had to endure the social stigma of standing in a different queue from those parents whose parents could afford to pay.

Edwards’ work is situated in a particular time and place and may be more accessible to some audiences then others. However, this sense of distance is diminished in a piece of work called Refrainthat Edwards has created in collaboration with National Theatre Wales. At 2pm every day, the exhibition is activated by the voice of Edwards’ mum who reads a live radio play that is directly transmitted from her flat in Cardiff. The radio play was scripted by Edwards and explores notions of place, politics and class through narrations of his mums own experiences of growing up mixed with his own recollections and found text (Duchamp again). |

Although not part of the exhibition, Edwards’ social media activity acts as an extension of the dialogue; in one particular instance he re-tweets a post by the charity Arts Emergency ‘For the past forty year with no change, young people from privileged backgrounds have been over 5 times more likely to attend University, and 4 times more likely to make it in the creative industries. 40 YEARS NO CHANGE. Take that in. All the money spent, all the talk. Amazing’.

As a counterpoint to the above, Edwards’ exhibition is staffed by curators and early career artists as part of the Arts Council of Wales Invigilator Plus programme. All of the invigilators have been given accommodation and are paid a living wage allowing the opportunity to be accessible to all, perhaps change is on the horizon after all.

All in all, what Edwards’ manages to achieve perfect blend between materials and concept. His work maintains honesty through the authentic and competent use of materials. After all, what can really be more authentic than a mother’s voice? It is through Edwards’ personal histories we are led into a poetic enquiry of place, politics and class. Whereas other artists in the Biennale have tackled concerns at a macro level, Edwards’s work is distinctly rooted. To use Barthe’s term, it is this rootedness that acts as a punctumand has the ability to pierce or cut through.

Among the grandeur of Venice we are reminded that class and social mobility is still an issue; it is a conversation that should never have fallen off the table. While Edwards may have been able to transcend the circumstances relating to his upbringing, we are reminded that there are many more who are not able to do so.

Undo Things Done was curated byMarie-Anne McQuay in conjunction with lead organisation Tŷ Pawb and commissioned by the Arts Council of Wales. The exhibition runs from May 11 until November 24 at Santa Maria Ausiliatrice, Venice.

As a counterpoint to the above, Edwards’ exhibition is staffed by curators and early career artists as part of the Arts Council of Wales Invigilator Plus programme. All of the invigilators have been given accommodation and are paid a living wage allowing the opportunity to be accessible to all, perhaps change is on the horizon after all.

All in all, what Edwards’ manages to achieve perfect blend between materials and concept. His work maintains honesty through the authentic and competent use of materials. After all, what can really be more authentic than a mother’s voice? It is through Edwards’ personal histories we are led into a poetic enquiry of place, politics and class. Whereas other artists in the Biennale have tackled concerns at a macro level, Edwards’s work is distinctly rooted. To use Barthe’s term, it is this rootedness that acts as a punctumand has the ability to pierce or cut through.

Among the grandeur of Venice we are reminded that class and social mobility is still an issue; it is a conversation that should never have fallen off the table. While Edwards may have been able to transcend the circumstances relating to his upbringing, we are reminded that there are many more who are not able to do so.

Undo Things Done was curated byMarie-Anne McQuay in conjunction with lead organisation Tŷ Pawb and commissioned by the Arts Council of Wales. The exhibition runs from May 11 until November 24 at Santa Maria Ausiliatrice, Venice.

Visit to Agastya International Foundation

In February 2019 I had the opportunity to visit Agastya International Foundation in Andhra Pradesh, India. Agastya's mission is to 'spark curiosity, nurture creativity and instil confidence' in economically disadvantaged children and government school teachers by bringing innovative hands-on science education, project based and peer-to-peer learning to schools, towns and villages across India. It was a truly inspirational visit and I was fortunate to have the opportunity to deliver Creative Learning training to some of their staff. Below is a few snippets from the training and some reflections from the participants.

Creative learning: a journey on many levels

|

Creativity is an essential skill for young people in the 21st century; governments and think tanks all point towards its importance for economic growth. However, to focus solely on the economic imperative for creativity would be a shortcoming. Creativity has a positive impact on wellbeing; the act of creation and realisation is often accompanied by a sense of personal empowerment and agency. Even though many of the Lead Creative Schools projects happened over just a few months, I have seen young people undergo transformative journeys; ones that broaden their horizons, shift their perspectives and ultimately change their destinations.

|

The Lead Creative Schools scheme has been about teachers as well as pupils. Many teachers have been reinvigorated by working alongside creative practitioners which has often brought about a shift in their teaching practice. When commenting on the Welsh education reform journey, the OECD said that the new curriculum will need a different type of teaching professional. It feels that those who have adopted creative learning into their practice are embodying some of this difference.

I am delighted that the Welsh Government have decided to continue working with the Arts Council of Wales to fund a second phase of the creative learning through the arts programme. It is an exciting time to be working with schools and teachers as they prepare for a transformative new curriculum.

I am delighted that the Welsh Government have decided to continue working with the Arts Council of Wales to fund a second phase of the creative learning through the arts programme. It is an exciting time to be working with schools and teachers as they prepare for a transformative new curriculum.

A journey is more than a simple act of travelling from one place to another: it is an act of transformation, a process of change. With the start of any journey there can be that sense of trepidation but this is often surpassed by the anticipation of adventure and reward. Our social encounters with others can often energise and propel us forwards, so can a sense of doggedness and persistence. However, occasionally it feels good to linger, to take things in slowly, to move at our own pace. During these reflective moments, perspectives shift as internal connections are formed, as such, what we once perceived as our destination can often change.

For the last four and a half years I have worked for the Arts Council of Wales on the Lead Creative Schools scheme, part of the wider creative leaning through the arts programme. The scheme has involved creative practitioners such as, animators, actors, architects, dancers and musicians working with teachers to nurture creativity in young people. Teachers and pupils have experimented with the enquiry methods, processes and approaches that creative practitioners use in their everyday practice and applied it to their learning; this unique approach has been about far more than a simple exchange of technical art skills.

For the last four and a half years I have worked for the Arts Council of Wales on the Lead Creative Schools scheme, part of the wider creative leaning through the arts programme. The scheme has involved creative practitioners such as, animators, actors, architects, dancers and musicians working with teachers to nurture creativity in young people. Teachers and pupils have experimented with the enquiry methods, processes and approaches that creative practitioners use in their everyday practice and applied it to their learning; this unique approach has been about far more than a simple exchange of technical art skills.

Return to The Jungle

In late 2016, the migrant camp known as The Jungle was cleared of inhabitants. Many of the migrants who had made The Jungle their home had been transported to alternative camps across France, but what happened to the others? I started to wonder think about the migrants I had met the previous year (see earlier blog post), where were they now? Even though I knew the site was closed, I somehow felt compelled to return.

For many of the Calais locals, the migrant camp had been a blight; an unlikely home for thousands of migrants and an unwelcome attraction for the world's media. The town seemed to be undergoing a period of growth and repair. There was more conversation, more vigour, and a general lightness to the town. You had the feeling that the migrant camp represented a point in history that the people of Calais would rather forget, or erase entirely.

I headed towards the site of the former camp on foot; retracing the steps I had taken 18 months earlier. Last time I did this journey I passed scores of migrants; this time I did not pass a single one - they had gone, all of them! As I neared the site I came across occasional traces; old bottle tops, discarded lighters, and an abandoned sleeping bag. The road bridge that demarcated the former entrance to The Jungle beckoned. I walked under the bridge and emerged on the other side but rather than the sea of activity I witnessed last time, I was presented with a vast expanse of emptiness. The sandy soil stretched into the distance, occasionally carved by the deep tracks of a bulldozer. The site had been completely cleared, all of the people had gone and their dwellings removed; not a single one remained.

I headed towards the site of the former camp on foot; retracing the steps I had taken 18 months earlier. Last time I did this journey I passed scores of migrants; this time I did not pass a single one - they had gone, all of them! As I neared the site I came across occasional traces; old bottle tops, discarded lighters, and an abandoned sleeping bag. The road bridge that demarcated the former entrance to The Jungle beckoned. I walked under the bridge and emerged on the other side but rather than the sea of activity I witnessed last time, I was presented with a vast expanse of emptiness. The sandy soil stretched into the distance, occasionally carved by the deep tracks of a bulldozer. The site had been completely cleared, all of the people had gone and their dwellings removed; not a single one remained.

The inside of the road bridge still hosted Banksy's mural of Steve Jobs; it somehow felt tired and without purpose, mirroring the spent fires and discarded belongings littered around its base. It also served as a reminder that the spotlight that once shone on this place has moved on and sought a new spectacle elsewhere.

As I walked across the site, the remnants of the camp and its former inhabitants were still visible on the surface; blankets, toothbrushes, tampons, cutlery, food cartons, tablets - all of the essentials needed for a very basic mode of living. Among the debris there were also some cogent reminders that the camp also housed children; toy cars, LEGO blocks, colouring books and jigsaw pieces.

Perhaps the playing was not reserved just for children, there were also dominoes, scrabble pieces, playing cards and deflated footballs among the debris; a way to pass the time for those in an extended state of limbo. There were numerous empty lager cans and bottles littered across the site. I thought about why these may have been drunk; was it a way to socialise with new found friends, a drink at the end of a long day or perhaps a way to forget, just for a while?

Perhaps the playing was not reserved just for children, there were also dominoes, scrabble pieces, playing cards and deflated footballs among the debris; a way to pass the time for those in an extended state of limbo. There were numerous empty lager cans and bottles littered across the site. I thought about why these may have been drunk; was it a way to socialise with new found friends, a drink at the end of a long day or perhaps a way to forget, just for a while?

As I wandered across the site, I came across six people in fluorescent jackets. They were in the process of forensically cleaning the site. This was more than a simple cleansing operation; it was a process of total erasure. Before long all physical traces of the migrant camp would be gone, I was told that they wanted to return the site to nature. The nature had already started to return to the site and you could hear a variety of birds chirping in the nearby bushes; the sound seemed somewhat discordant in this vast empty space. An even more unlikely return to nature was represented by a small patch of the site where some onions had been discarded. In an improbable turn, a handful of these onions had actually managed to take root and were starting to grow; this seemed poignant somehow.

Humans always leave traces and despite the efforts to erase the physical remnants of the site a discernible presence remains. This is a place that is traumatised, one that is psychologically scarred. The makeshift dwellings that once stretched towards the sky in supplication were destroyed in the most brutal manner; the beacons of hope and aspiration flattened. I wonder if the bulldozers even hesitated when they razed the rudimentary mosques and church to the ground.

Places hold memories and this is a place that can never forget.

Places hold memories and this is a place that can never forget.

Elysium Gallery: A Wildly Confident Teenager

There is nothing worse than visiting a gallery that has had a former heyday and is now in decline; that moribund feeling simply clings to you. In contrast to these galleries are those that are on the rise; they pulse and beat, imbuing you with a feverous energy. Their incandescence works its way into the imagination, giving rise to stratospheric ideas. These galleries have an emerging identity, like a wildly confident teenager who is willing to take risks; there are moments of utter brilliance, a prodigy in the making perhaps. Naturally there are also those moments to reflect upon, but where others would dwell, the wildly confident teenager simply moves on. It’s a fast paced ride, but one that you, and others, can’t help being drawn into.

Elysium is an example of a wildly confident teenager. A relatively young artist led organisation, Elysium are embarking on their most ambitious project yet, the opening of a 4000 sq. foot venue in Swansea City Centre. A former nightclub seems to be the perfect match for such an organisation. The new venue consists of two exhibition spaces, a test bed area, a workshop space and a café bar. Perhaps the exceptional part of the story is the way that the project is funded.

Over the last 12 years, Elysium has worked with local landlords and housing charities to renovate vacant premises within the city centre and turn them into artist studios. Elysium now occupies four buildings in the city centre and represents the largest studio complex in Wales; 83 studios and counting... Elysium’s new venue will be funded by rent from their studio complex and sales generated in the café bar; no more waiting for hand-outs from the bank of Mum and Dad, this teenagers got themselves a job.

With a diverse artist community (and those who have come along for the ride) ideas are never a shortcoming at Elysium; many are enacted, and quickly. The new venue has gone from conception to realisation within just 6 months.

Elysium is an example of a wildly confident teenager. A relatively young artist led organisation, Elysium are embarking on their most ambitious project yet, the opening of a 4000 sq. foot venue in Swansea City Centre. A former nightclub seems to be the perfect match for such an organisation. The new venue consists of two exhibition spaces, a test bed area, a workshop space and a café bar. Perhaps the exceptional part of the story is the way that the project is funded.

Over the last 12 years, Elysium has worked with local landlords and housing charities to renovate vacant premises within the city centre and turn them into artist studios. Elysium now occupies four buildings in the city centre and represents the largest studio complex in Wales; 83 studios and counting... Elysium’s new venue will be funded by rent from their studio complex and sales generated in the café bar; no more waiting for hand-outs from the bank of Mum and Dad, this teenagers got themselves a job.

With a diverse artist community (and those who have come along for the ride) ideas are never a shortcoming at Elysium; many are enacted, and quickly. The new venue has gone from conception to realisation within just 6 months.

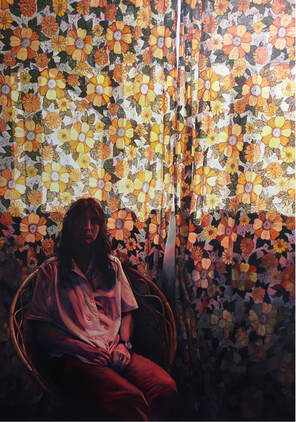

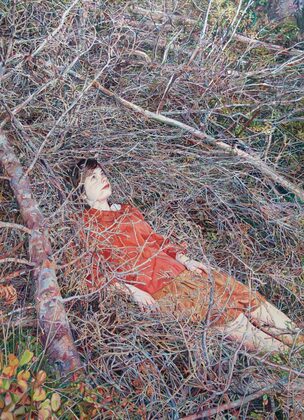

Images from the opening exhibition, Good Morning Midnight by Ruth Murray

Another example of ideas being turned into reality can be seen in BEEP (biennial exhibition of painting). Initiated in 2012, BEEP represents the only prize in Wales exclusively for painting. From humble beginnings, the last manifestation of BEEP, attracted 550 entries from 10 countries, with selected works shown across five partner venues. It is anticipated that 2020 will represent the largest BEEP ever with 7 partner venues across the UK already committed to being involved.

It’s not all plain sailing, the teenage years never are, Elysium face many of the perennial problems that other galleries do. Dare I say it – how do you widen your audience? Perhaps some Google Analytics or Facebook analysis – yawn. Elysium’s solution to this problem is refreshingly simple – the creation of a mobile gallery. Perhaps as adults we overthink, making things more complicated than they need to be. Converted from an old demonstrators van, the mobile gallery has been used to take Elysium’s work out into the community. The mobile gallery seems typical of Elysium’s ‘do and see’ approach with its purpose in a positive state of flux; it has already been used for learning and engagement work, but also doubles up as a low-fi, but highly visible method of marketing and publicity.

I’m not sure if I want Elysium to grow up, its all to easy to imagine the quick decision making and the ‘do and see’ approach disappearing into a quagmire of bureaucratization as it grows. Maybe its course will be very different, and it will remain the perpetual teenager. For now, it’s time to simply enjoy its youthful energy.

It’s not all plain sailing, the teenage years never are, Elysium face many of the perennial problems that other galleries do. Dare I say it – how do you widen your audience? Perhaps some Google Analytics or Facebook analysis – yawn. Elysium’s solution to this problem is refreshingly simple – the creation of a mobile gallery. Perhaps as adults we overthink, making things more complicated than they need to be. Converted from an old demonstrators van, the mobile gallery has been used to take Elysium’s work out into the community. The mobile gallery seems typical of Elysium’s ‘do and see’ approach with its purpose in a positive state of flux; it has already been used for learning and engagement work, but also doubles up as a low-fi, but highly visible method of marketing and publicity.

I’m not sure if I want Elysium to grow up, its all to easy to imagine the quick decision making and the ‘do and see’ approach disappearing into a quagmire of bureaucratization as it grows. Maybe its course will be very different, and it will remain the perpetual teenager. For now, it’s time to simply enjoy its youthful energy.

What does it take to make the Artes Mundi shortlist?

Just Between Us - Thomas Williams

Engagement with others is not always an easy task, especially when it extends across differences in race, religion, language and citizenship status. Just Between Us is an exhibition that explores active engagement across physical thresholds as well as these metaphorical boundaries.

The Trinity Centre acts as an important hub to asylum seekers and refugees located within the city of Cardiff; situated just a few hundred metres away is the contemporary art gallery, G39. Despite sharing a close physical proximity, the two sets of users of these institutions rarely, if ever mix. Just Between Us chronicles Thomas Williams attempt at reaching out from the G39 gallery to engage with the asylum seeker and refugee community at the Trinity Centre.

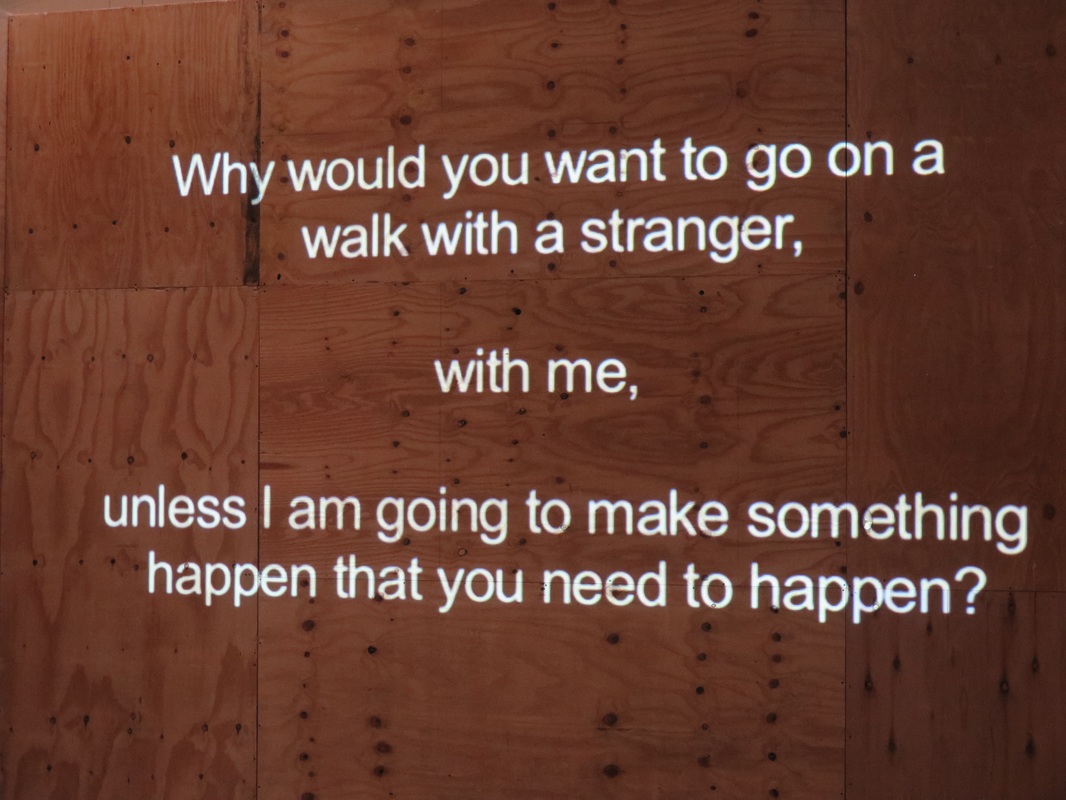

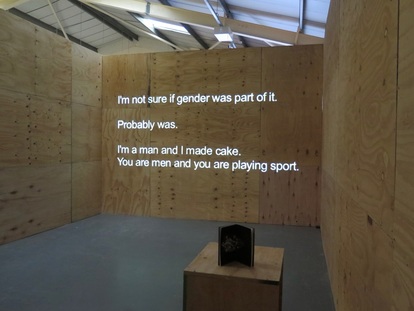

Thomas' primary medium for the exhibition is text, which is projected onto the wall of the Unit #1 space at G39. The text exposes the artist's difficulties in attempting to engage with the asylum seeker and refugee community at the Trinity Centre.

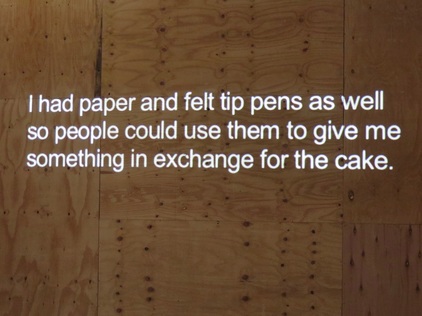

Principally, the exhibition is an acknowledgement of ‘failure’ by the artist. We read that on one particular occasion, Thomas had made cakes with the intention of attempting an exchange with members of the community at the Trinity Centre,

'I had paper and felt tips as well so people could give me something in exchange for the cake'.

The Trinity Centre acts as an important hub to asylum seekers and refugees located within the city of Cardiff; situated just a few hundred metres away is the contemporary art gallery, G39. Despite sharing a close physical proximity, the two sets of users of these institutions rarely, if ever mix. Just Between Us chronicles Thomas Williams attempt at reaching out from the G39 gallery to engage with the asylum seeker and refugee community at the Trinity Centre.

Thomas' primary medium for the exhibition is text, which is projected onto the wall of the Unit #1 space at G39. The text exposes the artist's difficulties in attempting to engage with the asylum seeker and refugee community at the Trinity Centre.

Principally, the exhibition is an acknowledgement of ‘failure’ by the artist. We read that on one particular occasion, Thomas had made cakes with the intention of attempting an exchange with members of the community at the Trinity Centre,

'I had paper and felt tips as well so people could give me something in exchange for the cake'.

With further reading, we learn that Thomas was unable to make the exchange as his overwrought sensitivity manifested itself,

'I'm a man and I made cake. You are men and you are playing sport'.

Unable to bring himself to make the exchange, Thomas took the cakes home,

'so much cake to eat'.

In a separate episode, we read that Thomas had arranged a series of walks for members of the Trinity Centre as a way of introducing them to the local area and promoting social cohesion. But, despite the artist texting them all the night before, 'nobody showed up'. Once again, the artist's anxieties came to the fore, and he asks himself, 'why would you want to go on a walk with a stranger?'

'I'm a man and I made cake. You are men and you are playing sport'.

Unable to bring himself to make the exchange, Thomas took the cakes home,

'so much cake to eat'.

In a separate episode, we read that Thomas had arranged a series of walks for members of the Trinity Centre as a way of introducing them to the local area and promoting social cohesion. But, despite the artist texting them all the night before, 'nobody showed up'. Once again, the artist's anxieties came to the fore, and he asks himself, 'why would you want to go on a walk with a stranger?'

From a socially engaged perspective, the entire volume may rightly be considered a ‘failure', a difficult to wield but critical tool in the artist’s armory. However, the artist employs another important tool in their armory, that of ‘resilience’. This is acknowledged in a soliloquy by the artist, who asks himself, 'now to work out how to use this new episode of failure in a creative and useful way?'.

Looking beyond the parameters of socially engaged practice, Thomas' work is more effective and articulates the essence of human engagement across boundaries and its potential pitfalls; we are able to recall our own psychological pain in similar situations. His work reminds us of the difficulty in active engagement and the potentially debilitating effect our sensitivities to others might have in this process.

Thomas delivers work that requires active consumption rather than a passive form of spectatorship. It is the artist’s commitment to his cosmopolitan imagination that engenders a sense of ethical and social responsibility, despite adversity that should be noted for its ability make us question our own relationship to others with/in the world.

Looking beyond the parameters of socially engaged practice, Thomas' work is more effective and articulates the essence of human engagement across boundaries and its potential pitfalls; we are able to recall our own psychological pain in similar situations. His work reminds us of the difficulty in active engagement and the potentially debilitating effect our sensitivities to others might have in this process.

Thomas delivers work that requires active consumption rather than a passive form of spectatorship. It is the artist’s commitment to his cosmopolitan imagination that engenders a sense of ethical and social responsibility, despite adversity that should be noted for its ability make us question our own relationship to others with/in the world.

Calais: Where Worlds Collide

Having seen the news coverage of the migrant camps in Calais I felt a compulsion to see them with my own eyes and hear first hand about the lives of people living there.

I’d be lying to say I wasn’t slightly apprehensive about going and wondered whether it would be a safe place for me to visit. However, this apprehension was counterbalanced by a pressing need to know more about the situation there.

On arriving at the ferry port I got a bus into the town centre. On route, I passed several groups of migrants. It was as if two separate worlds had collided, with holidaymakers travelling in one direction and migrants seeking to travel in the other.

I set off on foot towards The Jungle (the name adopted by the residents of the largest migrant camp in Calais). I noted that some parts of Calais had seen better days as I passed abandoned buildings and run down hotels. However, on the outskirts of Calais I passed through what seemed like a fairly affluent housing estate; surely I was in the wrong place. The houses ended and I entered an industrial park. A long road ran through the industrial park with a trickle of migrants passing in both directions. I followed the road away from the town and gradually saw an increasing number of migrants. As I passed under a road bridge I emerged into The Jungle.

I’d be lying to say I wasn’t slightly apprehensive about going and wondered whether it would be a safe place for me to visit. However, this apprehension was counterbalanced by a pressing need to know more about the situation there.

On arriving at the ferry port I got a bus into the town centre. On route, I passed several groups of migrants. It was as if two separate worlds had collided, with holidaymakers travelling in one direction and migrants seeking to travel in the other.

I set off on foot towards The Jungle (the name adopted by the residents of the largest migrant camp in Calais). I noted that some parts of Calais had seen better days as I passed abandoned buildings and run down hotels. However, on the outskirts of Calais I passed through what seemed like a fairly affluent housing estate; surely I was in the wrong place. The houses ended and I entered an industrial park. A long road ran through the industrial park with a trickle of migrants passing in both directions. I followed the road away from the town and gradually saw an increasing number of migrants. As I passed under a road bridge I emerged into The Jungle.

There were people everywhere. All of the photographs I had previously seen didn’t prepare me for the physical experience of standing within the camp.

I felt some migrants watching me as I entered the camp, it seemed the they were just as apprehensive about me as I might have been about them, and with good reason. Not everyone that enters The Jungle has come with good intentions. I learned later about the far-right groups who had previously visited the site and assaulted a number of migrants. I also learned about the brutality of the French police, a story corroborated by numerous migrants and also my friend who visited three days later and told me about their presence on site with pepper spray in hand. And of course, there are the people smugglers, attempting to extort money from these desperate individuals.

As I wandered further into The Jungle I realised I wasn’t in any danger. I struggled to imagine what distress some of these individuals must have experienced to make them want to cross continents in search of a safe haven; they were not looking for trouble. I felt guilty at my initial thoughts of apprehension.

A circuitous road runs throughout the camp from which tents stretch out in all directions, spilling over into the dunes and wooded areas. The tents vary in size, dimension and construction; perhaps an indication of how long the inhabitants intend to stay in The Jungle. Most of the tents were inhabited but some appeared abandoned, presumably by those who had successfully made their journey to the UK or elsewhere.

I felt some migrants watching me as I entered the camp, it seemed the they were just as apprehensive about me as I might have been about them, and with good reason. Not everyone that enters The Jungle has come with good intentions. I learned later about the far-right groups who had previously visited the site and assaulted a number of migrants. I also learned about the brutality of the French police, a story corroborated by numerous migrants and also my friend who visited three days later and told me about their presence on site with pepper spray in hand. And of course, there are the people smugglers, attempting to extort money from these desperate individuals.

As I wandered further into The Jungle I realised I wasn’t in any danger. I struggled to imagine what distress some of these individuals must have experienced to make them want to cross continents in search of a safe haven; they were not looking for trouble. I felt guilty at my initial thoughts of apprehension.

A circuitous road runs throughout the camp from which tents stretch out in all directions, spilling over into the dunes and wooded areas. The tents vary in size, dimension and construction; perhaps an indication of how long the inhabitants intend to stay in The Jungle. Most of the tents were inhabited but some appeared abandoned, presumably by those who had successfully made their journey to the UK or elsewhere.

I was struck by one particular tent surrounded by potted plants and flowers. Did these flowers and plants give a sense of normality or perhaps dignity to their residents amidst the chaos?

To call The Jungle a ‘camp’ is perhaps an overstatement and suggests a purpose built facility. In reality, it is disused piece of wasteland that has been increasingly inhabited by migrants.

To call The Jungle a ‘camp’ is perhaps an overstatement and suggests a purpose built facility. In reality, it is disused piece of wasteland that has been increasingly inhabited by migrants.

There is very little infrastructure within The Jungle apart from one enclosed compound (right). The French authorities provide one meal a day for the residents from this compound and offer accommodation to a small number of women and children there. About 95% of the residents within The Jungle live outside of this compound.

Apart from this limited infrastructure and a handful of portable toilets there are very few other facilities within The Jungle; life remains rudimentary.

Apart from this limited infrastructure and a handful of portable toilets there are very few other facilities within The Jungle; life remains rudimentary.

I saw several migrants collecting or carrying wood, presumably to make fires to cook on. I was acutely aware that these fires would soon be needed for warmth as the winter months approached.

The lack of infrastructure was clearly starting to cause problems and rubbish had started to accumulate at various points across the camp.

In this photograph, migrants are wheeling canisters of water back to their tent that they have filled from a mains pipe that runs through the camp.

The necessary enterprising of migrants is evident throughout the camp. This makeshift shop had been built by one of The Jungle residents and is one of many that can be found on site. The vendor had previously been a shop owner in his home country of Syria. Although this makeshift shop tells the tale of innovation in a desperate situation it worryingly suggests a sense of permanence.

As well as individual enterprise, there are also strong notions of community and cooperation throughout The Jungle, as demonstrated by this church built by its residents; a mosque has also been built on the site. the varying backgrounds, languages and religions within the camp, you might expect there to be problems between its various residents. From what I could see, this was simply not the case, a sense of solidarity and camaraderie was palpable.

In the photograph to the left, migrants are gathered around an electricity supply charging their mobile phones.

Fortunately there were those within the camp who were trying to make life more bearable for its inhabitants. Medicins du Monde had a First Aid tent on site which also served as an information point.

Medicins du Monde also offered Art lessons as a form of therapy to residents within The Jungle. They told me that many residents found these Art lessons extremely beneficial as a form of escapism from their everyday concerns. Furthermore, they acted as a useful instrument to help migrants learn new language skills.

Fortunately there were those within the camp who were trying to make life more bearable for its inhabitants. Medicins du Monde had a First Aid tent on site which also served as an information point.

Medicins du Monde also offered Art lessons as a form of therapy to residents within The Jungle. They told me that many residents found these Art lessons extremely beneficial as a form of escapism from their everyday concerns. Furthermore, they acted as a useful instrument to help migrants learn new language skills.

Clearly, there was some hostility within the town towards the migrants, especially by those who ran businesses. However, there were many other residents that were willing to help. In the image below a local Calais resident is delivering wooden pallets to The Jungle and is distributing them as fairly as he can amongst the migrants.

Despite the harrowing circumstances which surround them I found the residents I had met in the Jungle to be friendly and amiable and extremely appreciative of those willing to help them. For the most part, they retained high spirits and the drive and determination to search for a better life despite the obstacles in their way. Several even managed to make light jokes about their current situation, dire as it was.

I spoke to individuals from Eritrea, Sudan, Syria and Pakistan many of which kindly shared their personal stories, including the reasons why they had left their home countries and their hopes and aspirations for the future. It seems that world affairs, which can often seem so remote and abstract, took on concrete meanings through the personal stories of the residents in The Jungle.

I spoke to a man from Parachinar located on the Pakistan/Afghanistan border who had left his village after ISIS had invaded. As a male nurse, he had seen the mutilated bodies lying within the hospital following an ISIS attack. He told me that he had no option to leave his village, fearing for his life. I asked him why he wanted to travel to the UK and he told me that he had heard that asylum seekers would be well received and given a place of sanctuary. I wish I could have told him that this was categorically the case.

I spoke to individuals from Eritrea, Sudan, Syria and Pakistan many of which kindly shared their personal stories, including the reasons why they had left their home countries and their hopes and aspirations for the future. It seems that world affairs, which can often seem so remote and abstract, took on concrete meanings through the personal stories of the residents in The Jungle.

I spoke to a man from Parachinar located on the Pakistan/Afghanistan border who had left his village after ISIS had invaded. As a male nurse, he had seen the mutilated bodies lying within the hospital following an ISIS attack. He told me that he had no option to leave his village, fearing for his life. I asked him why he wanted to travel to the UK and he told me that he had heard that asylum seekers would be well received and given a place of sanctuary. I wish I could have told him that this was categorically the case.

Adverts for Facebook

I don’t ever remember seeing an advert for Facebook back in the day, everyone seemed to be talking about it and it was free, so I joined. I enjoyed the early days, re-acquainting with old friends, posting photos and status updates, and hovering between ‘single’, ‘in a relationship’ and ‘it’s complicated’. Over time, I moved from what can only be described as an ‘active’ user to a passive, but fairly nosy observer.

The banality of people’s posts has never ceased to amaze me; images of palaeo-breakfasts, maps of cycle routes and those annoying status updates, like ‘guess what I’ve been doing?’ Don’t get me wrong, I’ve wasted plenty of hours looking at what others have posted and watched my fair share of pet videos and pointless memes.

We’ve always blamed Capitalism for narrowing our choices – a Berger quote springs to mind ‘Capitalism survives by forcing the majority, whom it exploits, to define their interests as narrowly as possible’, but given the repetitive nature of posts on Facebook, it seems that we are capable of narrowing down our choices all by ourselves.

It seems that Facebook is a virtual Panopticon whose self-regulating behaviour has given rise to cat memes, VDA’s (virtual displays of affection), mundane brain dumps and more. Jeremy Bentham proposed the idea of the Panopticon, an imagined institutional building and a system of control; the general principle is that inmates are unable to tell whether or not they are being watched and are therefore compelled to act as if they are being watched at all times. Thus they are effectively compelled to regulate their own behaviour.

I am reminded of another Berger quote, although I’ve adapted somewhat, ‘Social Media users must continually watch themselves. They are almost continually accompanied by their own image. While socialising with friends or on a picturesque holiday in the South of France they can scarcely avoid imagining what a post might look like. From their earliest post they have been taught to continually survey themselves. And so, they come to consider the surveyor and the surveyed within them as two constituent yet always distinct elements of their identity’.

The concept of social media suggests that it might have a social function. But what type of glue is Facebook? I would propose that rather than being some kind super glue that holds us together, it is a bit more like your pound shop variety; looks like the real things but does a terrible job.

We’ve all read about the anxieties that some people have faced as a result of using social media, and my own journey from active user to nosy parker probably came about as a I realised that I was using social media as a vehicle for self-validation.

But for me, it was during the Brexit debate that the ‘glue’ really came under scrutiny. Due to Facebook’s algorithmic chicanery, it seemed that all of my friends shared the same view as me. I was looking forward to some spirited debate on-line, the opportunity to challenge and disagree. – but I was denied this opportunity.

Social bonds are formed through shared opinions but also through the understanding of difference. Being denied this opportunity to interrogate difference, makes for a passive and quite mundane experience – time to rethink the algorithm I think.

These revelations over the last two years about what Facebook does with our personal data raises even further questions about the social media experience. Given that many users are leaving Facebook, I thought it might be worth helping Zuckerberg out with some ‘real’ adverts for Facebook.

The banality of people’s posts has never ceased to amaze me; images of palaeo-breakfasts, maps of cycle routes and those annoying status updates, like ‘guess what I’ve been doing?’ Don’t get me wrong, I’ve wasted plenty of hours looking at what others have posted and watched my fair share of pet videos and pointless memes.

We’ve always blamed Capitalism for narrowing our choices – a Berger quote springs to mind ‘Capitalism survives by forcing the majority, whom it exploits, to define their interests as narrowly as possible’, but given the repetitive nature of posts on Facebook, it seems that we are capable of narrowing down our choices all by ourselves.

It seems that Facebook is a virtual Panopticon whose self-regulating behaviour has given rise to cat memes, VDA’s (virtual displays of affection), mundane brain dumps and more. Jeremy Bentham proposed the idea of the Panopticon, an imagined institutional building and a system of control; the general principle is that inmates are unable to tell whether or not they are being watched and are therefore compelled to act as if they are being watched at all times. Thus they are effectively compelled to regulate their own behaviour.

I am reminded of another Berger quote, although I’ve adapted somewhat, ‘Social Media users must continually watch themselves. They are almost continually accompanied by their own image. While socialising with friends or on a picturesque holiday in the South of France they can scarcely avoid imagining what a post might look like. From their earliest post they have been taught to continually survey themselves. And so, they come to consider the surveyor and the surveyed within them as two constituent yet always distinct elements of their identity’.

The concept of social media suggests that it might have a social function. But what type of glue is Facebook? I would propose that rather than being some kind super glue that holds us together, it is a bit more like your pound shop variety; looks like the real things but does a terrible job.

We’ve all read about the anxieties that some people have faced as a result of using social media, and my own journey from active user to nosy parker probably came about as a I realised that I was using social media as a vehicle for self-validation.

But for me, it was during the Brexit debate that the ‘glue’ really came under scrutiny. Due to Facebook’s algorithmic chicanery, it seemed that all of my friends shared the same view as me. I was looking forward to some spirited debate on-line, the opportunity to challenge and disagree. – but I was denied this opportunity.

Social bonds are formed through shared opinions but also through the understanding of difference. Being denied this opportunity to interrogate difference, makes for a passive and quite mundane experience – time to rethink the algorithm I think.

These revelations over the last two years about what Facebook does with our personal data raises even further questions about the social media experience. Given that many users are leaving Facebook, I thought it might be worth helping Zuckerberg out with some ‘real’ adverts for Facebook.